German observers sneered at what they saw as the comforts that were required to be lavished on French conscripts in order for the Assembly Nationale to pass the bill. The large-scale national debate over the extension of conscription from two to three years in France in 1913 demonstrated to German soldiers that the French army was an instrument beholden to republican politics. In order to have an army roughly the size of the German army, France needed to conscript nearly 85 percent of its eligible manpower Germany conscripted less than 50 percent of eligible young men. As a consequence, in the years before 1914, France struggled to match the size of the German army.

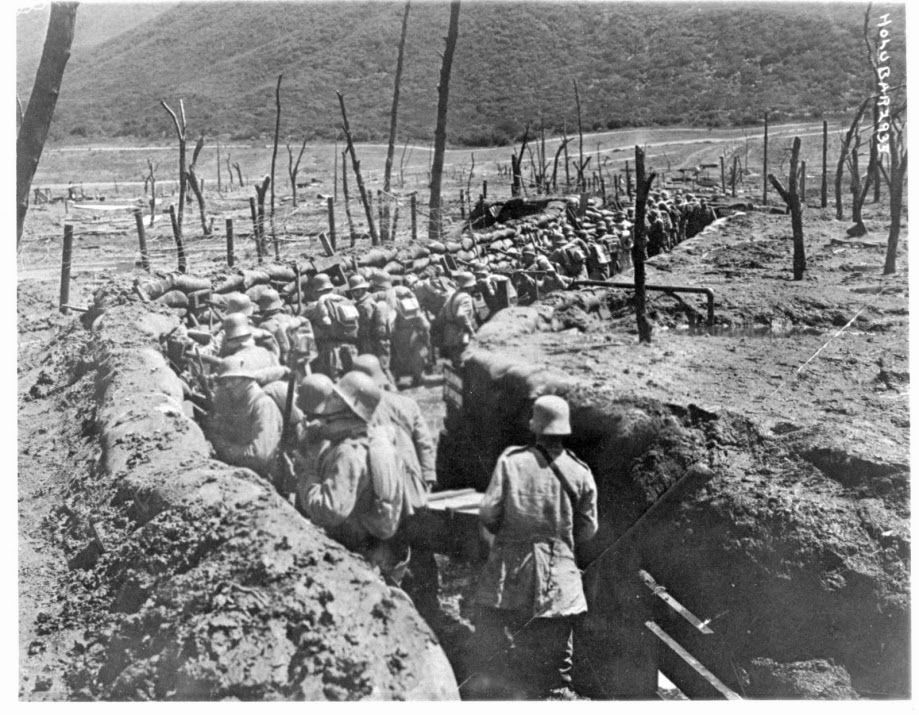

While the German population increased by some 25 million between 18, the French population only grew by several million. Unlike Imperial Germany after unification in 1871, the size of the population of Third Republic France stagnated. Moreover, German intelligence had long seen French manpower as being a strategic weakness. For an aristocratic Prussian officer, any political system that was built upon and reflective of the will of the people could not possibly stand up to considerable pressure. In common with many of his contemporaries, including those in the Intelligence Section of the German High Command, Falkenhayn saw the French republican political system as being fundamentally weak. While this goal may seem to play into a currently dominate myth of senseless slaughter and unimaginative generalship in the First World War, in fact, Falkenhayn’s strategic goals from the battle were subtle, and his approach represents perhaps one of the most sophisticated strategies of the entire war.įirst, Falkenhayn’s strategy at Verdun was built on certain assumptions about the French nation and its people. By the end of the year, close to 400,000 Frenchmen and 340,000 Germans had been made casualties in what was the war’s first deliberate battle of attrition.Īlthough historians have long debated the German goals for the battle, recently available archival evidence shows that from its inception, the German Chief of the General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, conceived of this battle as a means of ‘bleeding white’ the French army. The battle was also the first real battle of material waged by the German army: The 5th Army had at its disposal hitherto unheard of numbers of artillery pieces, mortars, and even flamethrowers, as well as the munitions needed for a drawn-out battle. During the course of the battle, some three-quarters of the French divisions and one third of German divisions cycled through the ‘hell of Verdun,’ as it was known by the participants on both sides. Between February and December 1916, the German 5th Army and the French 2nd Army were locked in a struggle, often over the loss or gain of a few meters of terrain. On 21 February 1916, the German 5th Army launch what was to become the longest battle of the war at the French fortress of Verdun.

#VERDUN BATTLEFIELD THEN AND NOW SERIES#

This series explores the German strategic, operational, and tactical planning for the battle. Indeed, for France and Germany today, the battle of Verdun is as synonymous with the First World War as the battle of the Somme is for Britain. Although it is not as well remembered in Britain today, the ‘hell of Verdun’ left an enduring mark on not only on the millions of Frenchmen and Germans who fought there, but also on their societies.

This month marks the 100th anniversary of the beginning of this battle, which would last, including French counter-offensives, until the end of 1916. This is the first of three posts covering German planning for Operation Gericht, their offensive at Verdun.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)